Licensing, certification and registration

Tony Minichiello

Maximis Communications Consultants

The Dictionary of Occupational Titles by the U.S. Department of Labor describes more than 12,000 occupations in the United States that have been classified by the nature of work performed, educational level, skills required and industry. To qualify for work in some of these occupations, a person must meet certain qualifications, including proof of educational credits, work experience and job skills. A governmental body, whether federal, state, county or local, may assume responsibility for licensing certain occupations to protect the health, safety and welfare of the public. These government bodies may establish standards for occupations that affect the residents of an area and license those in the occupation to produce revenue for government operations.

Occupational licensing is different from business licensing. An occupational license is issued to an individual to practice in an area, whereas a business license is issued to a company. In this context, the term "license" is used at the state level to include licensing, certification and registration. In the northeastern United States, for example, approximately 74% of the occupations that are regulated are licensed, 23% are certified and 3% are registered.

In other cases, occupations may be licensed by federal, municipal or county governmental units. In addition, professional certification through national certifying organizations may be either voluntary or mandatory for some occupations.

Governmental regulation of occupations can be a perplexing area. Some occupations, such as doctors, plumbers, electricians and engineers, are licensed. Other occupations, such as psychologists, firefighters and pesticide applicators, are certified. Still other occupations--lobbyists, carnival operators and hearing-aid dealers--need only to be registered.

To find out more about what occupations are regulated in your area, check the yellow pages of your telephone directory for government licensing, certifying and registering bodies. In addition, all states in the United States publish directory handbooks of occupations that require state licensing. Arranged alphabetically by commonly accepted job titles, these directories are issued by state occupational information coordinating committees. "These committees," according to the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, "are multi-agency coordinating bodies created by federal law to improve, through coordination and standardization, the development, quality and use of labor-market and career information for program planning, career decision-making and economic development."

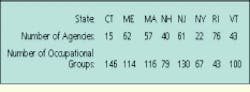

The ways in which occupations are licensed vary. Some states concentrate oversight and control in a few agencies, while others have a large number of agencies, boards and commissions responsible for licensing one or more occupations. In the northeastern United States, for example, oversight agencies and licensed occupational groups are distributed as follows:

Confusing terminology

The terminology used by agencies in regulating a person`s work activity can cause confusion and misunderstanding. Why are some occupations licensed, some certified and others registered? The definitions of these terms that appear in Occupational Licensing: A Public Perspective, by Benjamin Shimberg, can cast some light on the subject.

Licensing, according to Shimberg, "describes the process by which an agency of government grants permission to an individual to engage in a given occupation upon finding that the applicant has attained the minimum degree of competency necessary to ensure that the public health, safety and welfare will be reasonably well protected."

Before the license is granted, the applicant must meet certain requirements set forth in the law. These requirements usually involve training and experience, minimum age, years of formal education or academic degrees, a period of residence in the state and evidence of good moral character. Licensing is the most restrictive form of occupational regulation, because it prohibits anyone from engaging in activity without permission from a government agency.

"For certification, unlike licensure," says Shimberg, "the law does not prohibit individuals from engaging in the regulated occupation; however, it prohibits individuals from using a given title or from holding themselves out to the public as being `certified.` For example, anyone may practice or do accounting, but only those who have met state standards may call themselves Certified Public Accountants. In this way, the public is able to differentiate between accountants who have met the state standards and people who have not."

Applicants seeking voluntary certification must meet certain predetermined qualifications set by the certifying agency. Common requirements are graduation from an accredited or approved program; acceptable performance on a qualifying examination and completion of a specified amount of work experience.

Registration, on the other hand, is "a very general term sometimes meaning title control, or it may simply mean that the law requires all individuals who wish to engage in a given occupation register with a designated government agency."

Registration may only involve listing one`s name and address and paying a fee. As a rule, the law does not require individuals to pass an examination or show that they have met any predetermined standards, although bonding is sometimes required. Registration is used in situations where the threat to public health, safety or welfare is minimal.

Licensing is a source of revenue for a state government`s general funds. For example, in the state of Tennessee in 1990, 65,000 active licensed insurance agents paid an annual renewal fee of $25, resulting in over $1.5 million in revenue. Additional revenue came from initial applicants, who were charged a $50 fee, in addition to a $25 examination fee.

Telecommunications licensing

On average, 110 to 125 occupations require licensing by state governmental units in the United States; therefore, hundreds of occupations are not licensed and remain unregulated. Installation of telecommunications cabling is usually included in the latter group. With the exception of the state of Rhode Island, this area is currently not regulated at the state level in the United States. In fact, the design, installation and maintenance of voice, data, video and other low-voltage cabling, a multi-billion-dollar industry, is self-policing today. The industry moves ahead by establishing standards, codes and methodologies that address the needs of manufacturers, contractors and end users.

In July 1994, the Rhode Island state legislature passed into law specific legislation covering the licensing of telecommunications system contractors, technicians and installers. For the first time, Rhode Island made it illegal to contract or perform any telecommunications work without a license. Fees for licenses, examinations and other items range from $20 to $100 each. It is estimated that $150,000 to $200,000 in revenue in the first year will go to the state from this source.

Other states, such as New Jersey and Connecticut, have limited telecommunications wiring exemptions for qualified businesses. These exemptions may be granted by the state board of examiners of electrical contractors following an examination and certification process. In these states, however, no law precludes a licensed electrical contractor from performing telecommunications wiring.

Also, certain cities, including Boston, St. Petersburg, FL, and St. Louis, require that a permit and license be granted to businesses performing telecommunications work.

It would seem the U.S. telecommunications cabling industry is at a watershed. Should the industry continue to support the status quo, which is nonregulation, or should it support legislation in other states using Rhode Island`s procedure as a model?

In my view, the telecommunications cabling industry cannot avoid regulation. Such licensed and regulated occupations as electrical contractors and professional engineering groups are already in existence at its periphery. Through amendments to existing laws, such groups could make it illegal to perform any telecommunications work without approval or a limited exemption from the state board of examiners.

In reviewing my mail from various technical schools, colleges, equipment manufacturers and vendors, I see that several organizations are offering one-day to multi-day telecommunications courses. Upon completion of the curriculum, the enrollee is presented with a certificate of certification or registration. These certificate classifications are issued by non-governmental agencies and could be considered as diplomas. They do not, however, fulfill the need for an occupational certification or registration that is recognized nationwide.

Another group, the Building Industry Consulting Service International Inc., an organization of more than 5000 telecommunications professionals, focuses on the design and installation of telecommunications wiring systems. BICSI is active in all facets of the industry, including participation in telecommunications standards efforts. Recently, its governmental relations committee has been exploring the possibility of developing a licensing program that includes all pertinent state governmental boards and commissions.

BICSI is also creating a new registration program for cabling installers. Based on the organization`s successful Registered Communications Distribution Designer program for designers of telecommunications systems, the initiative will address the growing complexities of low-voltage installation and the critical part installation plays in total system performance. The BICSI Institute is developing a curriculum of generic installation courses leading to a registration examination that should be in place by the end of 1995.

Tony Minichiello is the principal of Maximis Communications Consultants, Concord, NH. An honorary life member of BICSI, he sits on that organization`s governmental relations committee and chairs its publication advisory committee.