Installing communications cabling in historic buildings

Protected by law, historic buildings call for a fresh approach to cabling

Jack Gehring

Unisource Systems Inc.

Dan Hanlon, P.E.

Office of the Architect of the Capitol

In modern buildings, communications pathways and spaces are usually provided as a matter of course. Suspended ceilings, raised floors, underfloor duct, hollow walls, modular partitions--these standard pathways make the routing of cabling simple and permit easy installation of horizontal and riser cable, connecting hardware and electronic equipment. Historic buildings, on the other hand, were not designed for the routing of telecommunications cabling--or, for that matter, for heating, air-conditioning, electrical, plumbing or other utilities.

Most historic buildings were constructed at times when social and technological conditions were much different. As recently as 100 years ago, the population of the United States was less than 70 million people. Cities were much smaller and the majority of the workforce was engaged in farming. A much smaller percentage of the population worked at white collar, service or office-based jobs. Manufacturing plants were powered by steam or water. Electricity and elevators, discoveries that made construction of tall buildings possible, did not appear until the end of the nineteenth century.

Only a few monumental and historic buildings are survivors of these earlier times. We appreciate their fine craftsmanship and solid construction, and admire them for having withstood the ravages of time and avoided the wrecking ball. Our goal when installing communications cabling in such buildings should be to provide, to the greatest extent possible, modern voice, data and video services while preserving architectural details and finishes. This calls for careful planning of pathways and spaces, including making allowances for future upgrading of the initial cabling system.

Utilities can share pathways

Heating, ventilation, air-conditioning and electrical systems face similar challenges in historic buildings. All utilities, in fact, compete for the same pathways and spaces. Often, routing and access solutions developed for these other utilities can be implemented for telecommunications as well. It is important to work closely with the architect and engineering and construction professionals during the initial design of the renovation to see if the different utilities can be coordinated.

Also keep in mind that federal historic preservation laws and guidelines must be followed for many buildings that fall into this category. These guidelines generally require that historic architectural details and finishes be preserved and that minimal visual impact be created by renovation or restoration.

For historic structures that contain office space, your main focus should be to provide reusable pathways and spaces within the building, so that modern premises distribution systems can be installed. The pathways and spaces should be reusable because, from a historic perspective, current concepts of telecommunications may prove to be fleeting. It would be shortsighted, therefore, to expect that today`s communications and distribution systems will be the last to be installed in a historic building. A historic building, in fact, may long outlast more modern structures because of the legal protection afforded it.

Even a multimode fiber backbone, Category 5 copper cabling or an IBM structured cabling system cannot be expected to last forever. Therefore, it is crucial that the telecommunications pathways and spaces designed for historic buildings allow the initial premises distribution system to be upgraded when necessary.

Installation techniques

There are several techniques available that can be used to install a premises distribution system in the pathways and spaces of a historic building. Some of them are:

Use existing chimneys or flues

Channel and then restore floors, plaster walls and ceilings

Construct false ceilings for cable raceways to run above hallways and rooms

Install a perimeter surface raceway

Purchase undercarpet cable

Utilize wireless local area networks and telephones.

Historic buildings were often originally heated by fireplaces, brick flues or metal pipes that distributed heated air, water or steam throughout the building. One or more fireplaces might have been built into each major room of a building. In the latter case, fireplace flues can sometimes be used to route heating, ventilation, air-conditioning, electrical and communications cabling to the upper floors of a building. Obviously, using the chimney as a cable raceway precludes its further use as a fireplace.

When using flues or chimneys for telecommunications cabling, a core penetration is made at the desired floor and an outlet is installed near the flue. Using fireplaces in this way may mean that cabling runs to the outlet must be routed from the cellar or basement vertically to individual rooms in the building. The common modern installation practice of using telecommunications closets cabled horizontally to outlets on the same floor may need to be replaced with a topology where closets in the basement serve vertical portions of several floors above.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, walls and ceilings were often constructed of plaster on brick or lath. This material can sometimes be channeled to provide space for flexible plastic or metal conduit. Decorative moldings and painted surfaces that are significant architectural features should not be channeled in this way.

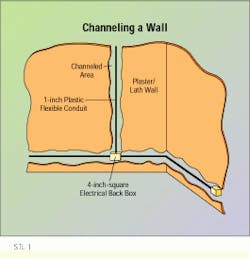

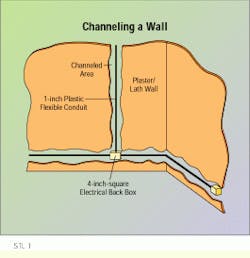

One such channeling technique involves channeling a plaster wall and installing flexible 1-inch conduit for cabling to electrical back boxes. Communications cabling is then pulled into the conduit and the channeled area carefully plastered over and repainted to match the original finished surface. Take photographs to document the work, and to aid in relocating the conduit later.

Hallways with sufficient ceiling height can sometimes be reconstructed with false ceilings that permit the installation of cable tray. A clearance of about 18 inches above the false ceiling is needed for installing cable tray or conduit for routing communications cabling. Consider leaving the original moldings and details in place above the false ceiling to allow future restoration of the original details. Concealed side or bottom access panels can be installed to provide working access.

Vertical distribution may be possible through architectural details such as pilasters-columnar structures built into walls. If pilasters are hollow, cable may be fished through them to reach offices on upper floors.

Another technique is to use surface raceway decorated to resemble wood or other molding that serves as the baseboard in a building. For example, surface raceway can be installed with wood molding along the top that matches the original baseboard in the space. Communications cabling can then be routed in the upper channel, and electrical cabling in the lower. Cable access to the raceway from strategically located punchdown blocks or patch panels is provided via electrical junction or pull boxes and flexible conduit channeled into the walls, which are then replastered or restored to original appearance.

Undercarpet cable systems can be installed to provide outlets in the interior of large rooms. This technique is typically used for power as well as telecommunications cabling. When power cabling is involved, carpet squares must be used per the National Electrical Code. Transition points from flat undercarpet cable to round horizontal cabling may be installed in perimeter raceway or electrical back boxes, which can be channeled into adjoining walls.

If the architecture is ornate or there are priceless architectural elements, you may want to consider a wireless LAN and a wireless telephone system. These systems are usually expensive and have limited capacity, but they may provide minimum disruption to a historic building or area.

Digging a channel in a plaster wall provides room for a communications conduit. The wall must then be restored to its original appearance.

Jack Gehring is a senior consultant at Unisource Systems Inc. (Washington, DC), and Dan Hanlon, P.E., is assistant director of engineering at the Office of the Architect of the Capitol (Washington, DC).